Austria’s 1B Liter Mega Reservoir: A Massive Win for Water

Dateline Neusiedl am Steinfeld, Austria

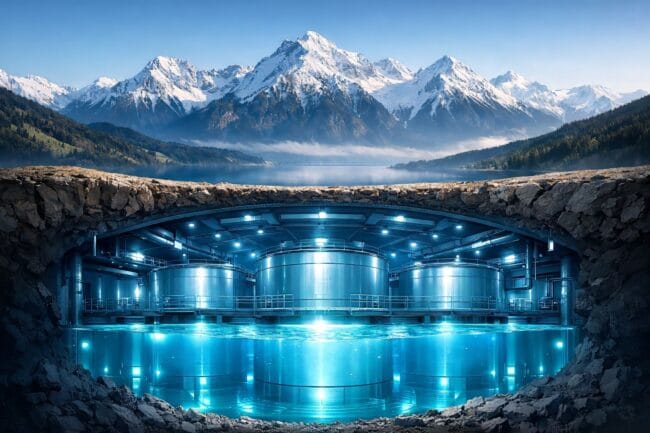

On a flat, wind-swept ridge south of Vienna, the construction site unfolds like a deliberate contest with time itself. Massive machines cut through the earth with mechanical precision, only for it to be reshaped, reinforced, and covered again.

Steel frames rise out of freshly poured concrete, gleaming faintly under a pale sky. Workers move in a carefully rehearsed choreography, checking levels, inspecting joints, and sampling concrete mixes engineered to hold water safely for decades. To the casual observer, it is a scene of organized chaos. To municipal engineers and planners, it is the meticulous assembly of a city’s lifeline.

The visible layers of the site, including cranes, scaffolding, and dust-filled air, tell only part of the story. Below, hidden from view, the underground chambers will soon house roughly one billion litres of drinking water. That staggering figure is more than a statistic. It is the tangible measure of Vienna’s commitment to resilience.

When city officials speak of preparedness in the face of climate change, this reservoir is what they mean. It is both a practical investment and a civic promise, a vault of security beneath the surface of daily life.

The expansion at Neusiedl am Steinfeld is a key pillar of the municipal strategy known as Vienna Water 2050. Its logic is straightforward yet profound. Vienna’s water begins high in protected alpine springs, fed through pipelines that rely largely on gravity. This reduces energy use while maintaining exceptionally clean quality.

Climate variability is reshaping familiar patterns. Snowmelt arrives earlier in the year. Summer heatwaves extend longer. Seasonal river flows become increasingly unpredictable. The reservoir converts this temporal abundance into a buffer, storing surplus water to ensure the city can sustain itself when natural supply dips.

“The employees on the construction site bear a high responsibility for securing Vienna’s water supply,” Paul Hellmeier, head of Wiener Wasser, told visiting reporters. “With this expansion we ensure that excellent drinking water will be available in sufficient quantity in the future.”

Plainly stated, the words emphasize function over flair. This project is not meant to be iconic. Its value lies in utility, foresight, and the quiet reassurance that beneath the ridge, Vienna’s water will flow uninterrupted, whatever the weather brings.

Making a billion litres comprehensible

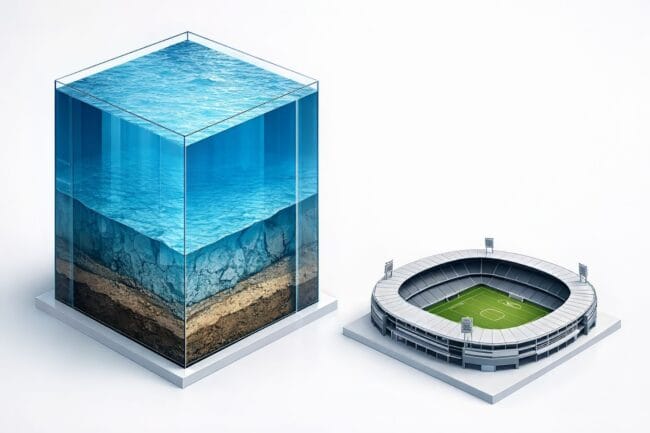

One billion litres is a number that flattens in the mouth. Officials and communicators have tried to make it visible by offering simple comparisons. Imagine a football pitch filled with water to a depth of 140 metres. The image is striking and helps people grasp the magnitude, but it has limits.

The reservoir at Neusiedl will not be a single column visible from the highway. It will be a system of modular chambers. Each chamber can be isolated, inspected, and cleaned without taking the whole facility offline. Modular design reduces operational risk, simplifies maintenance, and allows staged construction that keeps the city supplied while new chambers come on line.

The modularity also changes the practicalities of maintenance. If a sensor indicates an anomaly in one chamber, operators can seal it and keep the other chambers in service. If a leak is detected, the affected chamber can be emptied and repaired.

These design choices are technical but carry civic consequences. They determine whether the vaults will be a durable store of safe water or a liability that requires frequent intervention.

The people who turn concrete into public benefit

The site is full of tradespeople whose expertise is both ordinary and exacting. A foreman with decades of experience in tunnelling oversees the sequence in which concrete is poured and joints are sealed. He talks about tolerances in millimetres and the discipline required for cold weather pours.

A municipal planner frames the work in a different register. She speaks of intergenerational obligations and of buying time.

A nurse at a Vienna hospital thinks in outcomes. “If the reservoir gives us another week of supply during a summer spike, that is a week we can keep surgeries and dialysis running without emergency measures,” she said.

Local residents who live near the site measure the project in daily inconveniences. Truck routes change and the road hums with construction traffic. Noise arrives at different hours.

Those burdens are concentrated and immediate. The benefits, by contrast, are distributed and occasionally invisible. That gap between cost and benefit is the political heart of the story. A democratic city cannot assume that because a public good is diffuse in its benefits, the costs should fall on only a few.

Geology and engineering that matter

Large subterranean structures are not simply holes filled with water. They are engineered systems that integrate geology, hydrology, and public health.

Before a single metre of excavation began, geotechnical teams mapped bedrock, identified groundwater pathways, and tested soil strength. These surveys are essential. They determine the location and depth of chambers and the design of foundations. Mistakes at this stage can lead to subsidence, unexpected aquifer flows, or costly retrofits.

The concrete itself is chosen to meet drinking water compatibility standards. Reinforcement is specified to withstand long-term stress. Joints are designed to seal while allowing for thermal movement without compromising integrity. Ventilation and access points are arranged to prevent stagnation and allow routine inspection and cleaning.

Instrumentation throughout the chambers is dense. Sensors continuously monitor turbidity, temperature, and trace contaminants. Automated valves give operators precise control over inflow and outflow.

The engineering goal is to ensure that stored water remains potable without energy-intensive treatment. This is crucial because Vienna’s advantage lies in low-energy transmission. Much of the city’s supply is moved by gravity from high source pipelines. Preserving this low-energy profile helps maintain the city’s carbon footprint and enhances operational resilience.

Storage and climate management

Storage is not a substitute for other climate responses. It will not fix declining catchment rainfall, nor will it prevent upstream contamination.

It is, however, a management tool within a broader portfolio. When flows fluctuate, reserves provide time.

Time allows officials to prioritize medical facilities and critical infrastructure. It enables targeted conservation measures and the coordination of any necessary imports or transfers. Time reduces panic. That is the civic case for this kind of investment.

History offers warnings. Cities that have faced acute shortages often resort to abrupt rationing or emergency imports. Both carry high social and economic costs.

The Cape Town episode of 2018 remains an instructive example of the political and social strain sudden scarcity can cause. Storage reframes the problem. It does not make scarcity impossible. It makes scarcity manageable.

The environmental trade-offs

Excavation and construction come with visible impacts. Dust, noise, increased truck traffic, and temporary disturbance to local habitats are all part of the site’s daily reality. These effects are concentrated around the construction zone.

Responsible project management accepts these burdens and works to mitigate them. Measures include controlled runoff systems, strict groundwater monitoring, limits on truck routes through villages, and immediate restoration of disturbed land with native vegetation once work is complete.

The embodied carbon of concrete is a common criticism. Producing cement is carbon intensive.

The counterargument is that storage can reduce long-term operational emissions. By enabling gravity-fed transmission and avoiding the need for energy-intensive desalination or continuous pumping during protracted droughts, the reservoir can offset upfront carbon costs over decades.

The calculation is complex. It depends on operational models, the frequency of droughts, and the lifecycle of the infrastructure. Officials must make these calculations public so citizens can weigh short-term environmental costs against long-term resilience benefits.

Governance, transparency and accountability

Large capital works demand governance that is equally large and precise. Vienna has framed the reservoir within Vienna Water 2050, a strategy meant to tie capital spending to measurable outcomes. That framework is useful, but it should be complemented by transparent procurement documents, independent environmental audits, and a public dashboard reporting how many days of supply the city holds in reserve and what the leakage rates are.

A transparent audit trail is the most effective political safeguard against cost overruns and mismanagement. Citizens should be able to access procurement contracts and environmental impact studies online.

They should also be able to consult a regularly updated dashboard showing reservoir volumes and water quality metrics. Routine reporting prevents surprises and creates a factual basis for civic debate.

Money and political trade-offs

Public money has many claims. Schools, housing, and other municipal needs compete for limited funds. The political argument for preventive infrastructure is that planned capital outlays are often cheaper and less disruptive than emergency responses.

Investing in storage may appear expensive in the short term. Over the long term, it can be less costly than the social and economic damage caused by interrupted services.

That argument must be quantified. A credible cost-benefit analysis should compare the present value of construction and maintenance against the expected costs of emergency imports, rationing measures, and the economic losses associated with service interruptions.

These calculations depend on assumptions about the frequency of extreme droughts and the value of uninterrupted services. Making those assumptions explicit is an act of public responsibility.

When a project imposes concentrated burdens on a small group for benefits shared broadly, the social contract must be explicit. Local communities should receive clear, enforceable commitments on compensation and remediation. Timetables should be realistic and publicly published.

Community investment, whether in local infrastructure or in jobs and training tied to the project, can reduce resentment. If local people feel the project is happening to them rather than with them, opposition is likely.

A resident who lives near the works sums up the trade-off in plain terms. She tolerates the noise and the traffic because she wants her children to grow up in a city that does not run out of water. Her tolerance is conditional. She asks for clear timetables, limits on the worst disruptions, and meaningful remediation when construction finishes.

Lessons for other cities

No city should copy Vienna without regard to local context. Hydrology, governance capacity, and fiscal space differ from place to place.

Coastal cities that lack plentiful inland sources may find desalination the least bad option. Rapidly urbanizing cities with limited budgets may see higher impact from investing in leak detection and repairing existing networks.

That said, the logic of Vienna’s approach can translate. Protect and manage high-quality sources. Capture surplus when the hydrological calendar allows and store it. Use gravity transmission where the topography permits to keep energy costs low. Tie investments to transparent governance so citizens understand what is being delivered and why.

The small outcomes that matter

Infrastructure is often judged by big metrics. The human measure of success is smaller and more intimate.

A hospital that can continue critical operations during a heatwave. A bakery that can fire ovens and meet morning demand. A parent whose child can bathe without worry.

These small continuities are the practical value of a reservoir. They are the reason families vote for mayors and the reason municipal budgets are allocated to long-lived assets.

The project timeline and what to expect

The expansion is staged. Two additional chambers are scheduled to be completed by the end of 2028, adding roughly two hundred million litres of capacity.

Subsequent phases will bring the facility closer to the intended one billion litre mark. A staged approach is sensible. It spreads costs, allows for independent audits, and limits the risk that construction will require shutting down the entire system.

Each phase becomes a moment of public scrutiny, where the city can show what was promised and what was delivered.

Quality assurance and daily work

The vaults are guarded less by ceremony than by testing. Laboratory technicians run routine analyses for turbidity, microbiology, and trace organics.

Automated sensors feed continuous data into control rooms. The municipal certification authority conducts regular inspections.

Those daily checks are what make stored water a reliable resource rather than a risky stockpile. In engineering terms, the work is unglamorous but vital. In civic terms, it is the difference between public confidence and public anxiety.

Risk scenarios where storage matters most

Storage is most useful in scenarios that are prolonged but not instantaneous. Extended dry spells, a year with early snowmelt followed by a hot summer, or regionally correlated supply problems can all be mitigated by reserves.

Storage makes management possible. It allows supply managers to sequence conservation measures and protect critical services.

Storage is less relevant for sudden, catastrophic contamination events. Those require immediate isolation and treatment measures.

A multi-layered approach is therefore essential. Storage is one layer among monitoring, source protection, and emergency response.

What critics will ask

Critics point to the embodied carbon of the project, the concentrated burdens on local communities, and the perennial risk of cost increases. Those are reasonable concerns.

The responsible response from officials must be transparency and evidence. Publish lifecycle carbon assessments. Make mitigation plans public and subject them to independent review.

Establish durable oversight structures to monitor budgets and timelines. Saying that the project is necessary is not enough. Officials must prove that necessity is balanced with mitigation and that the project delivers long-term value.

A city building for a different future

The vaults that rise out of the ridge at Neusiedl are physical expressions of a municipal choice. They embody a view of cities as institutions that should buy time through investment when natural rhythms change.

That view requires both engineering skill and civic trust. The success of this project will be judged not by the size of its chambers but by the way the city uses what those chambers provide when stress arrives. Will the reserves be drawn down to buy time and then replenished? Will governance structures be strong enough to keep maintenance and oversight continuous? Will local burdens be minimized and benefits spread fairly?

If the answers to those questions are yes, the reservoir will have done its job. If the answers are no, it will be another large civic asset whose promise was lost to poor governance and inadequate mitigation.

On the ground, the work goes on. Concrete cures. Sensors are installed. Operators write procedures and rehearse scenarios. The foreman checks another joint and moves on.

Outside the site, a nurse counts the value of a reserve in the small outcomes of an ordinary workday. A resident down the road checks the timetable for truck movements and wonders whether the compensations will be timely and fair.

This is infrastructure in its practical mode. It does not require heroism. It requires maintenance, monitoring, and a steady civic commitment to transparency.

The measure of success will be whether, in a dry July that will almost certainly come at some point in the future, Vienna can choose rather than react. That choice is what storage buys. It is the final service that allows ordinary life to continue when the weather refuses to cooperate.

Editorial Disclaimer

The following article, Austria’s 1B Liter Mega Reservoir: A Massive Win for Water, is intended for informational and journalistic purposes. All reporting, analysis, and quotes have been gathered from publicly available sources, official briefings by Wiener Wasser, and on-site observations.

While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, water infrastructure projects are complex and subject to change due to construction schedules, technical challenges, or policy adjustments. Readers should understand that timelines, capacities, and technical details described in this article reflect current plans and projections and may evolve over time.

This editorial does not constitute professional engineering advice, investment guidance, or official municipal policy. It is a public-facing journalistic overview meant to explain the significance, human impact, and civic context of Vienna’s expanding water storage initiative.

FAQ – Austria’s 1B Liter Reservoir

Q: Why is Vienna building such a large reservoir?

A: The Neusiedl am Steinfeld expansion is part of the Vienna Water 2050 strategy. It ensures a reliable and safe drinking water supply for the city amid climate variability and a growing population by storing up to one billion litres of water.

Q: How big is one billion litres in practical terms?

A: To visualize the scale, one billion litres is roughly equivalent to filling a standard football pitch to a depth of 140 metres. The reservoir is modular, so it consists of multiple chambers rather than a single tank.

Q: How does the reservoir improve water security?

A: Stored water provides flexibility during dry periods, allowing the city to manage supply without emergency rationing. It protects hospitals, businesses, and residents by buying time to respond to shortages.

Q: What measures ensure water quality in the reservoir?

A: The chambers are built with high-quality concrete, carefully sealed joints, ventilation, and regular monitoring. Sensors track turbidity, temperature, and trace contaminants to keep water safe without energy-intensive treatment.

Q: Are there environmental or social impacts?

A: Construction creates temporary dust, noise, and traffic impacts. The project includes mitigation measures like controlled runoff, groundwater monitoring, restoration of disturbed land, and community compensation to balance local burdens with city-wide benefits.

Q: When will the new chambers be operational?

A: The first two new chambers are scheduled for completion by the end of 2028. Subsequent phases will expand capacity toward the full one billion litres target.

Q: Can this reservoir be used in emergencies?

A: Yes, it acts as a reserve in prolonged dry spells or supply fluctuations, allowing Vienna to maintain critical services. It is less relevant for sudden contamination events, which require immediate treatment interventions.

Q: How does Vienna’s reservoir compare to other cities?

A: While each city’s hydrology and infrastructure differ, Vienna’s approach demonstrates the importance of protecting high-quality sources, storing surplus, using gravity-fed distribution, and ensuring transparent governance. Other cities can adapt the logic rather than copy the exact blueprint.

Q: Who benefits from the reservoir?

A: All residents and services in Vienna benefit indirectly, especially critical facilities like hospitals, schools, and food services. Nearby communities bear short-term construction impacts but are compensated and supported through mitigation efforts.

Q: How can the public monitor the project?

A: Wiener-Wasser provides updates on construction progress, water quality, and reservoir levels. Public dashboards and environmental audits allow citizens to verify milestones and performance.

References

- Start of Construction for Global Mega-Project: An official press release from the City of Vienna detailing the ground-breaking for the world’s largest enclosed drinking water reservoir, aimed at securing the city’s future water supply via APA-OTS.

- Vienna Builds World’s Largest Enclosed Reservoir: A report on the strategic importance of the new reservoir in Neudörfl, Lower Austria, which will have a capacity of 300 million liters via The International.

- Securing Vienna’s Drinking Water Supply: An analysis of the engineering challenges and the long-term climate resilience goals of the project, ensuring water security for the growing metropolitan area via V.AT.

- Economic and Infrastructure Development: An overview of Vienna’s investment in high-quality spring water infrastructure, highlighting its status as a global leader in urban water management via Advantage Austria.

- Construction Progress Update (August 2025): An official progress report confirming that the expansion of the world’s largest enclosed tank is proceeding on schedule to meet the city’s rising demand via APA-OTS.