Coral Reefs: The Alarming 2026 Deadline for Global Collapse

The Silent Pulse of the Ocean

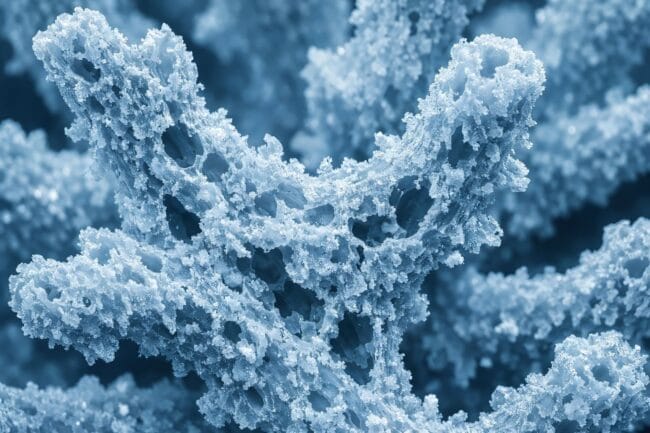

In the shallow, sunlit waters of the tropics, coral reefs extend like complex underwater cities across the ocean floor. These formations are not merely geological accidents but biological masterpieces of slow, deliberate construction. Tiny polyps, each measuring just a few millimeters, secrete calcium carbonate skeletons that accumulate over decades and centuries, creating massive three-dimensional structures capable of supporting a vast and intricate web of biodiversity. Branching corals, massive boulder formations, and delicate plate-like colonies create a labyrinth of microhabitats that provide essential shelter, feeding grounds, and breeding sites for a multitude of marine organisms, from microscopic plankton to apex predators.

Each layer of the reef provides distinct ecological services. The outer edge, constantly battered by waves, hosts species adapted to high-energy environments. The reef crest serves as a protective barrier, dissipating oceanic forces before they reach the lagoon. Behind this natural wall, calmer waters allow more delicate species to flourish.

Deep within the reef matrix, cryptic organisms such as sponges, worms, and crustaceans contribute to nutrient recycling and structural maintenance. This architectural complexity is not accidental but the result of millions of years of evolutionary refinement, where every crevice and overhang serves a purpose within the broader ecosystem.

The biological significance of these structures is staggering when compared to their physical footprint. Though coral reefs cover only 0.2 percent of the ocean’s surface, they host roughly 25 percent of all marine species at some point in their lifecycle. This concentration of life makes reefs the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, often referred to as the “rainforests of the sea.”

The comparison is apt: just as tropical rainforests support countless terrestrial species within towering canopies and layered understories, coral reefs create vertical habitats where pelagic fish, benthic invertebrates, and mobile predators coexist in a tightly woven network of interactions.

At the heart of this productivity is a remarkable mutualistic relationship. Photosynthetic dinoflagellates, known as zooxanthellae, live within the coral tissues. As sunlight penetrates the water column, it fuels photosynthesis within these algae, converting solar energy into essential carbohydrates.

These compounds are shared with the coral host, supporting skeletal growth, reproduction, and cellular maintenance. In return, the coral polyps provide protection and access to nutrients for their symbionts. This bond is the very foundation upon which the entire reef ecosystem is built. Without this partnership, the energetic demands of calcification and tissue maintenance would exceed what corals could obtain through filter feeding alone.

The symbiosis enables corals to thrive in nutrient-poor tropical waters, transforming sunlight into the structural foundation of one of Earth’s most productive ecosystems.

2026: The Thermal Threshold

As we approach the year 2026, this delicate biological balance is facing an unprecedented threat from rising global temperatures. Climate models have identified this specific year as a critical threshold for the survival of global reef systems.

The primary driver of this crisis is thermal stress. When sea surface temperatures exceed local summer maxima for multiple consecutive weeks, the internal machinery of the reef begins to fail. Thermal anomalies cause the symbiotic algae to malfunction, producing reactive oxygen species that damage both algal and coral tissues.

In a desperate response to this internal damage, corals expel their symbionts in a process known as bleaching. Without these algae, corals lose up to 90 percent of their energy intake. This leaves them metabolically compromised, pale, and highly vulnerable to starvation, disease, and eventually mortality.

The projections for 2026 are particularly alarming because they suggest that many reef systems will experience heat exposure far surpassing historical records. Scientists use Degree Heating Weeks to calculate the intensity and duration of this stress. The data indicates that bleaching events could become nearly annual in major regions like the Great Barrier Reef, the Coral Triangle, and the Caribbean.

Susceptibility to thermal stress varies significantly among species. Branching Acropora species are among the most fragile, often showing tissue mortality after just two to three weeks of elevated temperatures. In contrast, massive Porites corals display a higher tolerance, yet even they suffer from reduced growth rates and reproductive output under prolonged exposure.

Laboratory studies have revealed that corals rapidly mobilize their lipid and carbohydrate stores to sustain basic metabolic functions during these events. However, extended periods without photosynthetic input inevitably result in tissue necrosis and skeletal weakening.

This 2026 threshold represents a narrowing window where the frequency of heatwaves may outpace the natural recovery time corals need to rebuild their energy reserves and structural integrity.

Chemical Erosion: The Acidification Crisis

While rising temperatures attack the living tissue of the reef, a more insidious threat is transforming the very chemistry of the ocean. The absorption of increasing levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide is driving a phenomenon known as ocean acidification. As CO₂ dissolves into the sea, it reacts with water to form carbonic acid, which then breaks down into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions.

This chemical shift creates a more acidic environment, which directly depletes the availability of carbonate ions. For corals, these ions are the fundamental building blocks required for aragonite deposition, the process by which they grow their calcium carbonate skeletons.

The impact of this chemical erosion is profound. Experimental studies and field observations indicate that declining carbonate saturation can reduce coral calcification rates by 15 to 40 percent. This reduction is not uniform across the reef. Fast-growing branching corals, which provide much of the reef’s structural complexity, are particularly sensitive. They begin to exhibit slower skeletal deposition and thinner branches, making them significantly more susceptible to physical bioerosion and storm damage.

Even massive corals, which typically show more tolerance, experience delayed growth and a diminished capacity to recover from external disturbances.

The crisis is especially acute during the earliest stages of life. Coral larvae are highly vulnerable to acidic conditions, which impair the formation of their initial skeletal structures and lead to abnormal physical developments. Settling larvae struggle to attach to the seafloor and often produce skeletons that are weak, irregular, and malformed.

These defects limit juvenile survival and severely hinder the natural restoration of damaged areas. Population models suggest that regions with persistent low pH could see recruitment declines exceeding 50 percent over a single decade, leading to long-term degradation of the reef’s physical framework.

Ecological Cascades: The Unraveling Web

The decline of coral reefs is not a series of isolated events but a sequence of tightly coupled ecological cascades. In these complex environments, the loss of one functional group can propagate through the entire community, altering nutrient cycling and habitat availability.

Herbivorous fish are the unsung heroes of this balance. Scientists have identified a critical biomass threshold of 10 to 15 kilograms per hectare for these species. When herbivore populations fall below this level, the reef loses its ability to regulate algal growth.

Without enough grazers, fast-growing macroalgae begin to overgrow the coral surfaces, essentially smothering coral recruits and blocking the sunlight needed for symbiont photosynthesis. This shift creates a devastating feedback loop. Reefs with insufficient herbivory experience coral cover declines twice as fast as those with functional fish populations. The disruption of these trophic relationships, often driven by overfishing, accelerates overall ecosystem decline and prevents the reef from mounting a natural recovery.

Adding to this instability is the rise of lethal diseases. Stony coral tissue loss disease and white syndrome have been observed spreading rapidly across global reefs, causing extensive tissue necrosis and colony mortality.

These diseases are particularly deadly in areas already weakened by acidification or lack of herbivore grazing. Microbial community shifts associated with high-stress conditions facilitate the proliferation of pathogens, creating epidemic conditions that can erase substantial portions of living reef cover within months.

As the structural complexity of the reef vanishes, the fish and invertebrates that rely on these biological cities for shelter lose their refuge. This leads to a collapse in biodiversity that undermines the stability of the entire marine ecosystem.

Natural Fortifications: The Living Wall

Coral reefs are far more than biological wonders. They function as critical coastal defenses, providing a natural protective barrier against the relentless power of the ocean. These calcium carbonate structures are engineered by nature to dissipate up to 97 percent of incoming wave energy, a level of protection that many human-engineered sea walls fail to match.

Hydrodynamic measurements have demonstrated that within the first 50 meters of a reef crest, wave heights decrease by approximately 80 percent. This dramatic reduction in force significantly lowers the impact of storms and swells on adjacent coastlines, preventing shoreline erosion and shielding vital human infrastructure.

The effectiveness of reef-based protection is a matter of survival for low-lying island nations. Countries such as the Maldives, Kiribati, and Tuvalu are almost entirely dependent on their surrounding reefs to buffer the energy of the open sea. Without these intact reef systems, these nations would face direct, unfiltered exposure to storm surges, tidal flooding, and accelerated coastal erosion.

Predictive modeling indicates that the total loss of reef protection could increase wave-induced flooding and property damage by over 150 percent during extreme weather events. For these populations, the structural decline of the reef is an existential risk that threatens the habitability of their entire sovereign territory.

Unlike static human constructions, reefs act as dynamic barriers that can adjust their physical profile over decades in response to changing sea conditions. This self-repairing capacity offers an adaptive protection that artificial concrete structures cannot provide.

The three-dimensional complexity of the reef reduces wave velocities and disperses kinetic energy across multiple channels. This multi-layered absorption is critical during seasonal monsoon surges and cyclones, ensuring that both human communities and terrestrial ecosystems remain resilient against climatic extremes.

The Trillion-Dollar Economic Imperative

The potential collapse of coral reefs by 2026 is not only an ecological tragedy but also a profound economic crisis. Ecosystem service assessments now place the global annual valuation of reef services at over one trillion dollars. This massive figure encompasses commercial fisheries, global tourism, and the mitigation of coastal hazards.

Fisheries, in particular, rely on reefs as essential breeding and feeding grounds for numerous commercially important species. As the habitat degrades, juvenile survival rates plummet, leading to diminished yields and severe economic losses for both local and global fishing industries.

Tourism is another pillar of the reef economy that faces imminent collapse. Coral reefs attract millions of visitors annually for diving and snorkeling, driving revenue for hotels, transport services, and local businesses. Declining reef health and the loss of vibrant marine life directly reduce tourist numbers, creating cascading economic impacts across entire regions that depend heavily on reef-related travel.

Furthermore, the insurance and risk management sectors have begun to incorporate reef integrity into their financial assessments. Reefs that effectively absorb wave energy reduce the probability of catastrophic property damage from floods.

The loss of this natural insurance necessitates higher premiums and increases the need for massive public and private expenditure on engineered coastal defenses. Actuarial models now explicitly account for reef degradation when calculating expected losses from storm surges, highlighting the tangible financial value of these natural structures.

Investing in reef conservation is therefore an economically justified strategy. Preserving these structures yields returns that far exceed the initial costs by avoiding the long-term liabilities of damage and lost revenue.

Sparks of Hope: The Technological Counter-Offensive

Despite the dire predictions surrounding the 2026 threshold, a new era of marine science is providing tangible pathways for recovery. Emerging restoration technologies are no longer confined to small-scale laboratories but are being deployed as a global counter-offensive against reef decline.

One of the most foundational techniques is coral gardening. Fragments of healthy corals are cultivated in underwater nurseries under controlled conditions. By minimizing mortality from predation and environmental stress during their most vulnerable growth stages, these nurseries produce stable colonies ready for transplantation to degraded sites.

Complementing this is the process of microfragmentation, a technique that exploits the natural healing properties of corals. By dividing large colonies into tiny units, scientists increase the surface area relative to volume, which triggers a rapid growth response. These microfragments cover substrate much faster than intact colonies, potentially reducing the time required to achieve functional reef coverage by up to 50 percent. This speed is essential, as restoration must now outpace the accelerating rate of environmental degradation.

Perhaps the most ambitious frontier is assisted evolution. This method focuses on selectively enhancing coral resilience to the very thermal and chemical stressors that threaten them. Researchers have found that corals inoculated with heat-resistant symbionts show a 10 to 20 percent increase in survival rates during high-temperature events.

These resilient symbionts maintain photosynthetic efficiency even under stress, allowing the coral host to sustain energy production and calcification when others would bleach and perish. Additionally, engineered artificial reef structures are being used to mimic the three-dimensional complexity of natural systems, providing essential surfaces for larval attachment and refuge for marine fauna.

Guided by hydrodynamic modeling, these interventions ensure that water flow and larval delivery are optimized to maximize the efficiency of every restoration effort.

2026 as a Defining Threshold

The year 2026 represents a decisive intersection of ecological vulnerability, technological capability, and global policy. It is the boundary between a future where coral reefs continue to thrive as living archives of evolutionary history and one where they become relics of the past. The stakes extend far beyond the beauty of the underwater world. Coral reefs underpin global food security, protect the physical existence of low-lying island nations, and maintain the livelihoods of millions who depend directly or indirectly on healthy marine ecosystems.

The convergence of thermal stress and ocean acidification creates a dual assault on reef systems that previous generations of corals never faced. Historical records show that reefs have survived past climate fluctuations, but the current rate of change is occurring at a pace that outstrips natural adaptation mechanisms. Corals evolved over millions of years to cope with gradual environmental shifts, yet they now confront atmospheric carbon concentrations and temperature increases that have accelerated dramatically within a single human lifetime. The biological processes that sustained these ecosystems through past epochs are being overwhelmed by the sheer speed and magnitude of anthropogenic change.

Failure to act decisively in 2026 would trigger a catastrophic collapse that could become irreversible. While the challenges of warming, acidification, and ecosystem disruption are severe, the combination of restoration science, assisted evolution, and effective governance offers a narrow but real window for stabilization. The ocean’s pulse is still detectable in resilient areas where polyps continue to grow and fish populations maintain their ecological functions.

Scientists have identified reef regions that demonstrate greater thermal tolerance, possibly due to historical exposure to variable temperatures or unique genetic traits. These resilient populations represent natural reservoirs of adaptation that could be propagated through selective breeding and transplantation programs.

International cooperation will be essential to translate scientific innovation into meaningful conservation outcomes. The protection of coral reefs requires coordinated efforts across national boundaries, as many reef systems span multiple jurisdictions and are influenced by distant sources of pollution and carbon emissions.

Marine protected areas, when properly enforced, have shown the capacity to enhance reef resilience by reducing local stressors such as overfishing and coastal development. These protected zones serve as ecological refuges where depleted populations can recover and genetic diversity can be preserved.

Ultimately, the preservation of coral reefs is both a scientific challenge and a moral imperative. Every restored fragment and every resilient symbiont contributes to a broader global effort to preserve these functional pillars of the marine environment. Humanity’s capacity to combine technological innovation with immediate, coordinated global policy will dictate the outcome. There is no substitute for timely intervention.

The window of opportunity is closing rapidly, and the decisions made in the coming years will determine whether coral reefs persist as vibrant, productive ecosystems or fade into memory as cautionary tales of ecological neglect. Coral reefs remain salvageable if the global community takes responsibility today, ensuring that these living fortifications endure for generations to come.

The scientific tools exist, the economic case is clear, and the ecological necessity is undeniable. What remains is the collective will to prioritize long-term environmental stability over short-term economic convenience. The year 2026 is not merely a scientific projection but a call to action. The survival of coral reefs will serve as a measure of humanity’s ability to confront planetary-scale challenges with the urgency and cooperation they demand.

FAQ – Understanding the 2026 Coral Reef Crisis

Q: What are coral reefs and their role in the ocean?

A: Coral reefs are structures built by small organisms called polyps that secrete calcium carbonate over time. These formations create habitats for diverse marine species, regulate nutrient flows, and maintain ecological balance. Reefs support both microscopic and large animals, acting as essential hubs for marine biodiversity.

Q: Why is 2026 considered a critical year for coral reefs?

A: By 2026, the combination of rising sea temperatures and increasing ocean acidity is expected to put global reefs under severe stress. Scientists warn that bleaching events and structural weakening could become widespread, potentially causing long-term ecological damage if immediate interventions are not implemented.

Q: How does heat stress affect coral survival?

A: Elevated water temperatures disrupt the partnership between corals and their symbiotic algae. Corals may expel these algae, losing most of their energy supply. Without sufficient energy, coral growth slows, reproduction declines, and tissues become more vulnerable to disease and mortality.

Q: What impact does ocean acidification have on coral growth?

A: Ocean acidification reduces the availability of carbonate ions needed for corals to build skeletons. Calcification rates can drop between 15 and 40 percent. Young corals and larvae often develop weak or malformed skeletons, slowing natural reef recovery and reducing structural stability.

Q: How do coral reefs protect coastlines?

A: Coral reefs act as natural barriers against waves and storms. They absorb up to 97 percent of wave energy, with wave heights dropping around 80 percent within the first 50 meters of a reef crest. This protection is crucial for low-lying islands like the Maldives, Tuvalu, and Kiribati, shielding them from flooding and erosion.

Q: What is the economic importance of coral reefs?

A: Reefs provide ecosystem services valued at over 1 trillion dollars annually. They sustain fisheries, attract tourism, and reduce the costs associated with coastal protection. Degraded reefs threaten food sources, local economies, and infrastructure, highlighting their global economic significance.

Q: What methods are being used to restore coral reefs?

A: Restoration techniques include coral gardening, where fragments are grown in nurseries before transplantation; microfragmentation, which speeds up coral growth by splitting colonies; and assisted evolution, pairing corals with heat-resistant symbionts to improve survival by 10–20 percent. Artificial reef structures and hydrodynamic modeling help optimize recovery.

Q: Why is maintaining reef biodiversity essential?

A: A balanced ecosystem supports reef resilience. Herbivorous fish, at 10–15 kilograms per hectare, keep algae growth in check, allowing corals to thrive. Diseases such as Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease and White Syndrome can devastate weakened reefs, showing the importance of functional species populations.

Q: How can individuals and policymakers support reef conservation?

A: Governments can establish protected areas, enforce sustainable fishing, reduce pollution, and fund restoration programs. Individuals can minimize environmental impact through eco-friendly tourism, reducing carbon footprints, and advocacy. Coordinated action is crucial to prevent large-scale reef collapse and maintain ecosystem services.

Editorial Disclaimer

This article, Coral Reefs: The Alarming 2026 Deadline for Global Collapse, is produced for educational, informational, and scientific awareness purposes. It synthesizes current research, climate models, and expert analyses relevant to coral reef ecosystems as of 2026. While all information has been carefully verified, natural systems are complex and evolving, and neither the authors nor the publishers can guarantee absolute accuracy or predict future developments with certainty.

The content includes projections regarding coral bleaching, ocean acidification, reef restoration technologies, and economic valuations. These projections are based on the latest peer-reviewed studies and field observations but remain inherently uncertain due to environmental variability, technological constraints, and geopolitical factors. Readers should interpret the information as part of a broader, ongoing scientific discussion rather than definitive predictions.

Any references to financial valuations, coastal protection benefits, or restoration interventions are illustrative of current understanding and should not be considered professional advice for investment, policy, or legal decisions. The urgency and timelines described in this article reflect ecological risk assessments and scientific consensus on reef vulnerability rather than absolute deterministic outcomes.

The purpose of this publication is to inform and encourage awareness, research, and action regarding the state of global coral reefs. Conservation strategies, technological interventions, and policy measures mentioned are offered as examples of scientifically supported approaches, and their effectiveness may vary depending on local conditions and implementation.

References

- Coral Reef Ecosystems and Monitoring: An official technical overview of reef health, stressors, and conservation strategies from the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory via NOAA AOML.

- Micro-Fragmentation as a Restoration Tool: A peer-reviewed study detailing the effectiveness of micro-fragmentation technology in accelerating coral growth and restoring remote reef systems via ResearchGate.

- Global Coral Bleaching Event Analysis: A comprehensive report on the 2023–2025 global bleaching crisis, detailing the impact of rising ocean temperatures on marine biodiversity via Reuters/NOAA.

- Coral Reef Restoration Ecology: Research published in Frontiers in Marine Science exploring innovative coral gardening techniques and their long-term ecological benefits via Frontiers.

- Federal Partners Technical Memorandum: A 2025 strategic document outlining marine resource management and reef protection protocols in the Pacific region via OPD/NOAA.

- Machine Learning in Marine Conservation: A technical paper from 2025 discussing the application of AI and neural networks in monitoring coral reef degradation and recovery via arXiv.