Japan’s Luna Ring: Inside the $10T Lunar Energy Vision

As governments race to decarbonise power systems while electricity demand accelerates from artificial intelligence, data-centre expansion, and electrified transport, policymakers are confronting a stubborn reality. Terrestrial renewables are scaling rapidly, but intermittency, land-use constraints, transmission bottlenecks, and mineral supply chains continue to impose limits. Nuclear energy offers baseload capacity but faces regulatory, political, and financial barriers in many regions. Against that backdrop, Japanese researchers and aerospace planners have advanced one of the most audacious infrastructure concepts ever publicly discussed: Japan’s Luna Ring, a vast belt of solar collectors encircling the Moon and transmitting electricity wirelessly back to Earth.

The proposal does not resemble a single flagship mission or demonstration satellite. Instead, it sketches a planetary-scale industrial system that would integrate super-heavy launch vehicles, autonomous robotic construction, lunar mining, microwave power transmission, international regulatory regimes, and multi-decade financing structures measured in trillions of dollars. Its proponents describe it less as a near-term construction project than as a stress test for what twenty-first-century engineering and governance might eventually permit.

What follows is a detailed examination of how such a system would be built, what physical limits govern it, how much it might cost, and why it would reverberate far beyond the energy sector.

A Belt Around the Moon

At the centre of Japan’s Luna Ring is a deceptively simple geometric idea. Photovoltaic arrays would be deployed along a great-circle path near the lunar equator, forming an almost continuous band roughly 11,000 kilometres long. The Moon’s slow rotation, lack of atmosphere, and predictable illumination cycles make it attractive as a solar-collection platform. At the lunar surface, solar irradiance averages about 1,361 watts per square metre, essentially the same as in Earth orbit but without clouds, weather systems, or atmospheric absorption.

Early feasibility models assume photovoltaic conversion efficiencies between 25 and 35 percent, consistent with radiation-hardened multijunction gallium-arsenide cells already flown on spacecraft. If deployed over tens of thousands of square kilometres, such arrays could in theory generate power at multi-terawatt scales before accounting for conversion and transmission losses. That output rivals global electricity consumption today, which is on the order of 30 terawatts of continuous demand.

Unlike free-flying solar satellites in geostationary orbit, lunar installations could be mechanically anchored to regolith-based foundations. Lunar gravity, roughly one-sixth that of Earth, reduces structural loads and allows lighter truss systems for the same span. The absence of atmospheric drag eliminates the need for continuous station-keeping propulsion, one of the largest operating costs for large orbital structures.

The system would not be monolithic. Thousands of independent modules would comprise the belt, each with its own power electronics, beam-forming antennas, thermal radiators, and robotic maintenance units. This segmentation mirrors terrestrial high-voltage transmission networks, where redundancy is essential to prevent cascading failures across continental grids.

The Economics of a Ten-Trillion-Dollar System

The figure that most often dominates discussion of Japan’s Luna Ring is the estimated price tag: around ten trillion US dollars spread over multiple decades. That number aggregates launch services, lunar industrial plants, autonomous robotics fleets, wireless-power transmitters, Earth-based receiving stations, orbital relay satellites, and long-term operations.

Even with optimistic projections that fully reusable heavy-lift vehicles might eventually deliver cargo to lunar orbit for under 1,000 dollars per kilogram, transporting tens of millions of tonnes of equipment would alone imply expenditures in the multi-trillion range unless the vast majority of structural mass is produced on the Moon itself. Early phases would be far more expensive. Hardware delivered directly to the lunar surface today can cost well above 20,000 dollars per kilogram, and initial construction would depend heavily on such imported components.

Supporters frame the total in the context of terrestrial megaprojects. Global nuclear-power deployment over several decades has absorbed comparable cumulative capital in inflation-adjusted terms. Worldwide renewable-energy investment already exceeds one trillion dollars annually. From that perspective, a multi-decade, globally integrated lunar energy program would not be unprecedented in scale, though it would be unprecedented in complexity.

Operational expenditure also dominates long-term projections. Continuous monitoring, component replacement, orbital-traffic coordination, cybersecurity for command networks, regulatory compliance across jurisdictions, and insurance against rare but catastrophic failures all resemble the cost structures of satellite constellations or continental grid operators, multiplied by orders of magnitude.

Financing models envision blends of public investment, sovereign-wealth participation, infrastructure bonds, and long-term power-purchase agreements with utilities on Earth. Revenues would depend on guaranteed offtake contracts indexed to wholesale electricity prices and carbon-reduction incentives. Staged capital release tied to technical milestones, a standard tool in offshore-energy project finance, would likely be essential to manage risk at such unprecedented scale.

Building an Industrial Base on the Moon

No plausible version of Japan’s Luna Ring involves shipping the entire structure from Earth. In-situ resource utilisation, the practice of extracting and processing local materials, is central to its economic case.

Lunar regolith consists largely of oxides containing silicon, aluminium, iron, calcium, and magnesium. Using molten-regolith electrolysis, high-temperature reactors can separate these elements, producing oxygen as a by-product for life-support systems or rocket propellant. Aluminium alloys could form structural trusses, while silica-derived glass might serve as photovoltaic substrates or radiation shields.

Additive manufacturing would dominate fabrication. Large-scale sintering printers could fuse regolith into load-bearing blocks and track beds for surface transporters. Precision deposition systems would fabricate antenna reflectors, waveguides, and radiator panels. Operating such equipment in vacuum and reduced gravity introduces new process-control challenges: molten material behaves differently, thermal gradients are extreme, and microfractures can propagate unpredictably without atmospheric damping.

Quality assurance would rely on nondestructive evaluation techniques such as ultrasonic inspection and X-ray tomography, ensuring locally produced components meet aerospace tolerances. Production throughput would have to reach thousands of tonnes per year before expansion beyond pilot installations becomes economical.

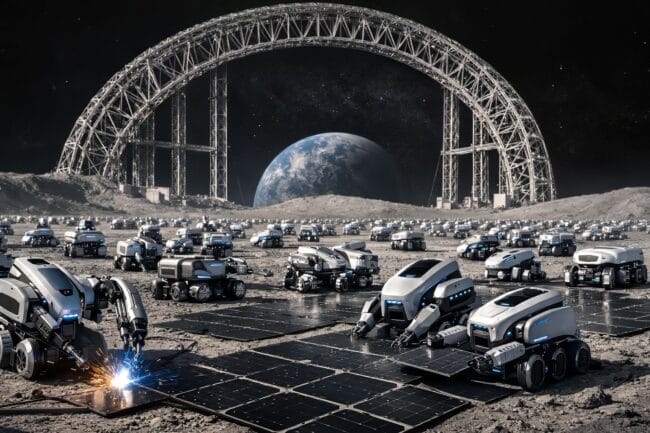

Autonomous Construction and Robotic Swarms

Human presence on the Moon remains constrained by radiation exposure, life-support logistics, and transport cost. Consequently, Japan’s Luna Ring presupposes a construction workforce composed primarily of autonomous and semi-autonomous machines.

Excavation rovers would feed regolith-processing plants. Assembly robots equipped with multi-arm manipulators, force-feedback sensors, and interchangeable tool heads would weld trusses, place photovoltaic tiles, and align antenna elements. Swarm architectures, in which hundreds of smaller units cooperate rather than relying on a few large machines, increase redundancy and parallelise work across vast sites.

Artificial-intelligence systems would coordinate these fleets, optimising routing, task allocation, inventory flow, and maintenance schedules. Communication delays of roughly 1.3 seconds one way between Earth and Moon mean that robots must make safety-critical decisions locally, without waiting for human approval. That requirement pushes autonomy far beyond current terrestrial construction robotics.

Software certification regimes comparable to those used in aviation would likely be extended to lunar systems. Formal verification of control algorithms, continuous anomaly detection, and layered fail-safe modes would be mandatory to prevent minor faults from propagating into large-scale structural damage.

Moving Hardware Across Cislunar Space

Even with mature lunar industry, early phases of Japan’s Luna Ring depend on a sophisticated transportation network between Earth and Moon. Architectures typically combine reusable super-heavy launch vehicles, propellant depots in Earth-Moon Lagrange points, and low-energy transfer trajectories that minimise fuel consumption.

Cargo arriving in lunar orbit would rendezvous with autonomous assembly platforms that pre-integrate modules before descent. Handling multi-hundred-tonne structures is mechanically simpler in microgravity than on the surface, reducing the number of individual landings required.

On the Moon itself, surface mobility might rely on rail-like transporters or maglev systems embedded in prepared tracks, capable of moving prefabricated sections hundreds of kilometres along the developing belt. Early operations would draw power from pilot solar fields or compact nuclear reactors until the ring itself begins supplying construction energy.

Reverse logistics are also part of the system. Failed electronics, damaged actuators, or experimental samples may be returned to Earth for forensic analysis, necessitating reusable ascent vehicles optimised for routine lunar operations rather than bespoke missions.

Harvesting Solar Energy Under Extreme Conditions

Photovoltaic arrays on the Moon must tolerate temperature swings from roughly minus 170 degrees Celsius during lunar night to plus 120 degrees in daylight. Multijunction cells provide high efficiency but require protective coatings against radiation-induced lattice damage. Dust is an equally severe problem. Lunar particles are electrostatically charged, abrasive, and prone to clinging to surfaces, degrading optical performance and mechanical joints.

Engineers propose electrostatic repulsion grids, vibrating coatings, or transparent conductive layers that periodically shake dust loose without manual cleaning. Power-conditioning electronics must convert direct current into high-frequency alternating signals for microwave generation at efficiencies above 95 percent; otherwise waste heat would balloon radiator requirements.

Energy buffering smooths output during eclipses or maintenance outages. Concepts include molten-salt thermal reservoirs, superconducting magnetic-energy-storage loops, or hydrogen produced by electrolysing lunar ice deposits and later reconverted through fuel cells.

Thermal management remains a defining constraint. In vacuum, heat can only be rejected by radiation, not convection. For gigawatt-class generation clusters, radiator areas comparable to the collector surface may be required, potentially doubling structural mass unless high-emissivity materials are developed.

Beaming Power Back to Earth

Wireless transmission is the most technically distinctive aspect of Japan’s Luna Ring. Microwaves in the 2.45- or 5.8-gigahertz bands are leading candidates because amplifier technology is mature and atmospheric absorption is relatively low in those windows. Phased-array antennas several kilometres across can focus beams with divergence angles of a few microradians, producing spot sizes tens of kilometres wide when they reach Earth.

Rectifying antennas, or rectennas, convert incoming radiofrequency energy into electricity at efficiencies exceeding 80 percent in laboratory demonstrations. The end-to-end system efficiency equals the product of photovoltaic conversion, DC-to-RF conversion, propagation efficiency, rectenna capture, and grid integration. Conservative estimates place the total between 10 and 15 percent, implying that multi-terawatt lunar generation would be required to deliver hundreds of gigawatts to terrestrial grids.

Laser transmission offers tighter beam control but suffers from greater atmospheric absorption and cloud interference, requiring orbital relay mirrors or globally distributed receiving stations. High-power laser emitters also pose unresolved thermal-management challenges.

Safety systems would be non-negotiable. Automatic beam shutoff would trigger if alignment drifts beyond defined thresholds, preventing energy densities that could harm aircraft, wildlife, or infrastructure. Continuous tracking of Earth’s rotation, orbital perturbations, and atmospheric refraction is required to keep beams precisely centred.

Networks, Cybersecurity, and Control

Operating a lunar energy belt demands communications infrastructure comparable to that of the largest terrestrial grids and air-traffic-control systems combined. High-bandwidth optical or Ka-band radio links would connect lunar operations centres to Earth, supplemented by relay satellites at Earth-Moon Lagrange points to maintain continuous coverage.

Millions of sensors would stream telemetry on structural loads, temperature gradients, power flows, and robotic health. Encryption standards would have to anticipate quantum-computing threats, and networks would be segmented so that failures or intrusions in one region cannot propagate system-wide.

Time synchronisation is particularly demanding. Phased-array transmitters separated by thousands of kilometres must coordinate to nanosecond precision. Atomic clocks distributed along the belt and cross-calibrated by laser links would underpin beam coherence.

Ground control centres would be geographically distributed across multiple countries to reduce vulnerability to geopolitical disruption or natural disasters, each capable of assuming full operational authority if others go offline.

Law, Governance, and Strategic Consequences

International treaties prohibit national appropriation of celestial bodies and restrict military uses of space. A lunar megastructure therefore raises questions about de facto territorial control, spectrum allocation for microwave transmission, and liability for accidents involving energy beams.

Licensing regimes would involve national regulators, international telecommunications authorities, and new multilateral agreements governing resource extraction. Transparency provisions could require publication of operational parameters, environmental monitoring data, and accident investigations. Dispute-resolution mechanisms modelled on maritime arbitration courts or pipeline-transit treaties would be essential to reassure investors.

Export-control laws complicate collaboration, as high-power microwave systems, launch vehicles, and autonomous robotics fall under dual-use classifications in many jurisdictions. Environmental assessments would evaluate how microwave flux interacts with Earth’s atmosphere and ecosystems, and how large-scale lunar industry affects scientific research sites.

If Japan’s Luna Ring ever reached maturity, it could reshape energy geopolitics. Countries hosting rectenna fields would gain strategic leverage analogous to pipeline transit states today. Wholesale electricity prices could fall during peak delivery windows, potentially displacing fossil-fuel generation and altering investment incentives for terrestrial renewables. Some scenarios envisage coupling lunar power to hydrogen production or large-scale desalination plants, extending its influence beyond electricity markets.

A Benchmark for Planetary-Scale Engineering

From a physical standpoint, no known law forbids a lunar solar belt transmitting power to Earth. Photovoltaics, microwave transmission, robotic construction, and regolith processing have all been demonstrated at small scales. The challenge lies in scaling each by six or seven orders of magnitude while synchronising their development across decades.

Cost estimates near ten trillion dollars remain plausible under conservative assumptions, though aggressive in-situ manufacturing and declining launch prices could materially alter long-term economics. At the same time, rapid progress in terrestrial renewables, grid-scale storage, and nuclear-fusion research may narrow the window in which lunar power offers unique advantages.

For now, Japan’s Luna Ring functions less as a blueprint for immediate construction than as a benchmark against which future space-energy strategies are measured. It encapsulates the outer edge of contemporary systems engineering, demanding coordination among governments, industries, financiers, and legal regimes on a planetary scale.

Whether or not such a belt is ever built, the analytical exercise of designing it forces a reassessment of what global infrastructure could look like in an era where Earth itself is no longer the only construction site.

FAQ – Japan’s Luna Ring

Q: What is Japan’s Luna Ring in technical terms?

A: Japan’s Luna Ring is a conceptual lunar infrastructure system consisting of a near-continuous photovoltaic belt around the Moon’s equator, roughly 11,000 kilometres in length. The system would generate electricity using high-efficiency multijunction solar cells and transmit that energy wirelessly to Earth via microwave or laser beams directed at large terrestrial rectenna arrays.

Q: Why place solar collectors on the Moon rather than in Earth orbit?

A: The Moon offers stable anchoring in low gravity, no atmospheric drag, and predictable illumination cycles. These conditions simplify structural design and eliminate station-keeping propulsion requirements typical of orbital platforms. The lunar surface also enables large-scale use of in-situ materials for construction, reducing the mass that must be launched from Earth.

Q: How much power could Japan’s Luna Ring theoretically supply to Earth?

A: Depending on surface coverage and photovoltaic efficiency, gross lunar generation could reach multi-terawatt levels. After accounting for DC-to-RF conversion, beam propagation, and rectenna efficiency, delivered power is commonly modelled in the hundreds of gigawatts range, comparable to the output of hundreds of large nuclear plants operating simultaneously.

Q: What frequencies are proposed for wireless transmission and why?

A: Microwave transmission in the 2.45 GHz and 5.8 GHz bands is favoured because amplifier technology is mature, atmospheric absorption is relatively low, and rectenna conversion efficiencies above 80 percent have been demonstrated experimentally. These frequencies also allow kilometre-scale phased arrays to maintain controlled beam divergence across Earth–Moon distances.

Q: How efficient would the entire energy chain be from lunar sunlight to terrestrial grids?

A: End-to-end efficiency is typically estimated between 10 and 15 percent. This figure combines photovoltaic conversion on the Moon, power-conditioning electronics, microwave generation, propagation losses, rectenna capture, and grid interconnection. Such losses imply that very large collector areas are required to achieve commercially meaningful output on Earth.

Q: How would construction be carried out without large human crews on the Moon?

A: The architecture relies on autonomous robotic swarms performing excavation, material processing, additive manufacturing, assembly, and inspection. Artificial-intelligence systems would coordinate thousands of machines in real time, enabling local decision-making due to Earth–Moon communication delays. Humans would supervise remotely and intervene only during anomalies or major reconfiguration.

Q: What lunar resources would be used to fabricate the structure?

A: Lunar regolith contains oxides of silicon, aluminium, iron, calcium, and magnesium. High-temperature electrochemical processes can extract these elements to produce metals for trusses, glass for substrates, and oxygen for propellant. Large-scale additive manufacturing would convert these materials into load-bearing components, antenna reflectors, and radiator panels.

Q: How would thermal control be managed in the lunar environment?

A: Waste heat from power electronics and microwave transmitters would be rejected through extensive radiator systems, as convection is impossible in vacuum. High-emissivity coatings, heat pipes, and radiative fins are essential. Thermal storage systems such as molten salts or superconducting magnetic loops could buffer output during eclipses or maintenance periods.

Q: What are the principal engineering risks associated with Japan’s Luna Ring?

A: Major risks include dust accumulation on photovoltaic surfaces, degradation from radiation, micrometeoroid impacts, large-scale thermal cycling, beam-pointing precision, and system-wide cybersecurity. Each risk demands dedicated mitigation strategies, such as electrostatic dust removal, segmented grid architectures, autonomous inspection drones, and quantum-resistant encryption protocols.

Q: How would safety be ensured for wireless energy beams aimed at Earth?

A: Beam intensities would be designed to remain below biological hazard thresholds outside designated rectenna zones. Automated shutoff systems would trigger if pointing accuracy degraded. Continuous aircraft tracking, orbital monitoring, and atmospheric modelling would prevent accidental exposure to concentrated microwave or laser flux.

Q: What legal frameworks would govern a project of this scale?

A: Governance would involve international space treaties, telecommunications spectrum regulation, environmental-impact assessments, export-control regimes, and new multilateral agreements for lunar resource utilisation. Liability rules for beam-related incidents and arbitration mechanisms for cross-border energy delivery would be central to maintaining political and financial stability.

Q: Why is the projected cost estimated near ten trillion dollars?

A: The figure aggregates decades of launch operations, lunar industrial facilities, robotic fleets, energy-transmission infrastructure, Earth-based receiving stations, cybersecurity systems, insurance, and maintenance. Even with aggressive reductions in launch costs and extensive in-situ manufacturing, cumulative capital expenditure for a planetary-scale system remains in the multi-trillion-dollar range.

Q: Is Japan’s Luna Ring considered feasible with current technology?

A: Individual subsystems such as photovoltaics, microwave transmission, autonomous robotics, and regolith processing exist today at experimental scales. The unresolved challenge is coordinated scaling by several orders of magnitude while maintaining reliability and economic viability over decades. Consequently, the concept is viewed as a long-horizon benchmark rather than an imminent construction program.

Editorial Disclaimer

This article, “Japan’s Luna Ring: Inside the $10T Lunar Energy Vision”, provides an analytical overview of the proposed lunar solar power system discussed throughout this text. All data regarding construction methodology, energy generation, wireless transmission efficiencies, robotic deployment, regolith-based manufacturing, costs, and projected timelines are derived from technical models, feasibility studies, and publicly available aerospace research. No part of Japan’s Luna Ring has been built, and all operational projections remain conceptual. While this piece reflects careful technical and economic analysis, actual outcomes may differ as materials, robotics, energy transmission methods, regulatory frameworks, and lunar operations evolve. The information is presented for journalistic and educational purposes only and does not constitute investment, policy, or financial advice.

References

- The Luna Ring Concept: The original architectural and engineering blueprint from Shimizu Corporation for a lunar-based solar power plant capable of supplying energy to Earth via Shimizu Corporation.

- Wireless Power Transmission for Space-Based Solar: A technical analysis of the microwave and laser transmission technologies required to beam energy across large distances via ScienceDirect.

- Japan’s 2025 Space-Based Solar Power Demonstration: An update on the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) upcoming mission to test orbital solar power collection and transmission via Space.com.

- Lunar Solar Energy Systems and Feasibility: A scientific paper exploring the potential of utilizing lunar resources to build and maintain large scale solar infrastructure on the moon via CiNii Research.

- Advanced Wireless Power Transfer for Orbital Operations: Research published in the Aerospace journal regarding the efficiency of energy transfer between celestial bodies and orbital receivers via MDPI.

- Strategic Evolution of Space Solar Power: A 2025 academic review detailing the geopolitical and environmental implications of shifting global energy production to the lunar surface via arXiv.